POSITION STATEMENTS

Osteoporosis Canada’s response to a recent publication about Osteostrong

Contributors: Dr. Adrian Lau, Dr. Lora Giangregorio, Dr. Claudia Gagnon, Dr. Laëtitia Michou, Dr. Alan Low, Dr. Emma Billington, Dr. Zahra Bardai, Dr. Vithika Sivabalasundaram, Dr. Rowena Ridout, Dr. Sandra Kim.

Recommendations from Osteoporosis Canada Rapid Response Team.

In February 2025, a new article was published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism (JCEM) regarding Osteostrong.

Osteostrong is described as “a bone-strengthening system implementing 4 devices and incorporating brief (10-minute), weekly, low-impact, and high-intensity osteogenic loading exercises”. This study claims that participation in Osteostrong for 10 minutes, once a week for 12 months resulted in improved bone mineral density (BMD) at the lumbar spine for women, whether they were on anti-resorptive therapies or not. The study also claims that “Osteostrong enhanced the effect of antiresorptive therapy on BMD and TBS (trabecular bone score*) of the spine, hip and femoral neck”.

However, it was brought to Osteoporosis Canada’s attention that there may be concerns about the validity and reliability of this study. These include flaws in the study design, non-adherence to reporting guidelines, and inappropriate analysis and reporting of results.

Some concerns about the Osteostrong study include:

- No clear objectives or hypotheses

- No information about ethical approval

- No clear statistical analysis plan

- No description of how the authors collected and analyzed all the data

- No evidence that the trial’s clinical protocol was registered online, for transparency

- Lack of efforts to reduce the risk of bias, such as randomization of participants and blinding of assessors

- Lack of considerations of confounding variables, such as the use of osteoporosis medications, and the duration and adherence of their use

- Lack of reporting standard outcomes, such as between group differences in bone mineral density at the hip or spine

Prior studies of Osteostrong are limited to observational studies with small sample sizes that are also at high risk of bias and are industry funded. There is one randomized controlled trial that compared devices like those used in Osteostrong facilities to a high intensity strength and impact exercise program. The devices did not increase bone mineral density compared to high intensity strength and impact exercise. Five people in the group that used the devices had spine fractures, compared to none in the exercise group.

The existing evidence regarding the benefits and harms of Osteostrong is of very low certainty and thus, Osteoporosis Canada cannot support recommendations regarding its use for fracture prevention based on existing research. There is a cost to participating.

Osteoporosis Canada also encourages health care professionals to analyze and assess these studies for themselves.

Those living with osteoporosis who are considering Osteostrong are encouraged to seek guidance from their health care professionals.

* Trabecular bone score (TBS) is an index of bone architecture, which is an indicator of bone quality.

Discontinuation of Denosumab FAQ

Authors: Dr. Adrian Lau, Dr. Laura Rothman, Dr. Joanna Sale, Dr. Jenny Thain, Dr. Teri Charrois

Recommendations from Osteoporosis Canada Rapid Response Team.

Many Canadians are taking denosumab injections for their bone health. However, there are some uncertainties about the use of this injectable osteoporosis medication.

How often do I need denosumab?

- Denosumab can be very effective in reducing fracture risk, and maintaining bone mineral density. However, in order to maintain these benefits, denosumab has to be administered without any interruptions.

- Denosumab should be given once every 6 months. It is safe if the dose is slightly delayed, but not more than 7 months after the previous dose.

- If a dose is delayed beyond 7 months after the previous dose, there is an increased risk of rapid bone loss and multiple vertebral fractures.

- Remember to plan your doses ahead of time, with your pharmacy, and healthcare professional who is administering your dose. You may also need to plan your doses around the time you may be out of town.

How long can I be on denosumab therapy?

- Once you have started on denosumab therapy, it is recommended that you continue the therapy for the “long-term”.

- The optimal duration of denosumab therapy is debatable. Research studies have shown denosumab therapy to be effective for up to 10 years. However, beyond 10 years, there is less data available. Talk with your physician about the optimal duration of therapy for you, as this may depend on factors specific to you.

Can I take denosumab indefinitely (forever)?

- We do not know the answer to this. There is little data about treatment with denosumab beyond 10 years.

- From current data, there appears to be an increased risk of rare side effects with prolonged, uninterrupted use of denosumab. These risks may increase with longer duration of use of denosumab.

- These rare side effects include atypical femur fractures (AFFs) and osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ).

- Hence, the decision about the duration of your therapy is a balance between the benefits (reduced fracture risk, maintained bone density), and potential harms (rare side effects) of ongoing therapy.

- Since the optimal duration of therapy is unknown, it is best to consult with your health care professional to determine what is best for your circumstances.

If I need to stop denosumab therapy, how can I do it safely? I was told that stopping denosumab therapy may result in significant bone loss and increased risk of spine fractures.

- Some people may choose to stop denosumab therapy because they are experiencing side effects, or if they would like to reduce their risk of AFFs or ONJ with ongoing therapy.

- There is evidence that suddenly stopping denosumab therapy can result in rapid decline in bone density and the development of new spine fractures.

- There are strategies that may help decrease the risk of these adverse outcomes. The optimal strategy for this is still unknown and is an ongoing area of research.

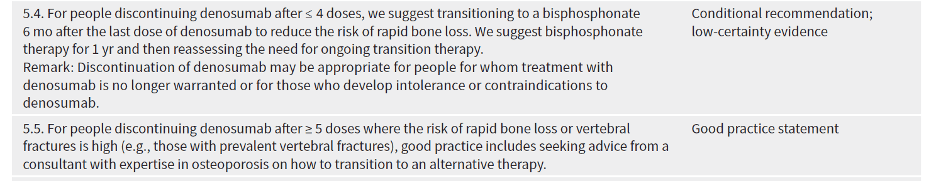

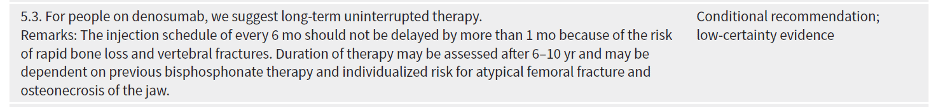

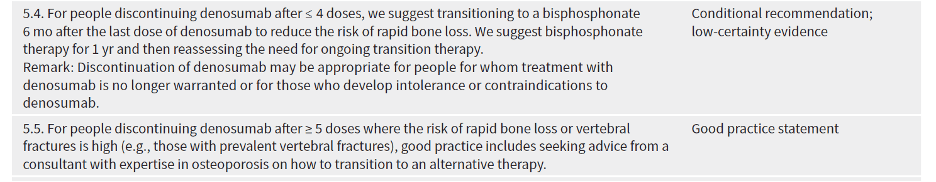

- In the 2023 Osteoporosis Canada Guideline, two recommendations are made, depending on how long you have been on denosumab for:

When I stop denosumab, do I need oral or intravenous (IV) bisphosphonate?

- The decision to use an oral or IV bisphosphonate may depend on many factors, including personal preference, the duration of your denosumab therapy, and your previous tolerance to bisphosphonate therapy.

- This decision should be made between you and your physician, based on your preference and considering the factors stated above.

Do I need more frequent bone mineral density testing or special blood tests (such as bone turnover markers) when I transition off denosumab therapy?

Your physician will help you with the transition off denosumab, including any investigations that are necessary. In some situations, your physician may refer you to a specialist with expertise in osteoporosis for a second opinion.

A repeat bone mineral density test (DXA scan) is necessary after stopping denosumab. However, the ideal timing for this test may differ for different people, and this decision should be discussed with your physician.

There is debate about whether checking bone turnover markers is helpful. This is a blood test that may not be readily available to all individuals, and its cost may or may not be covered by provincial/territorial health plans.

Should Bone Turnover Markers be routinely monitored when discontinuing someone from denosumab?

Contributors: Dr. Adrian Lau, Dr. Claudia Gagnon, Dr. Laëtitia Michou, Dr. Emma Billington, Dr. Zahra Bardai, Dr. Dr. Vithika Sivabalasundaram, Dr. Rowena Ridout, Dr. Sandra Kim, Dr. Suzanne Morin

Recommendations from Osteoporosis Canada Rapid Response Team.

Discontinuation of denosumab therapy is associated with rapid decline of bone mineral density, increase of bone turnover, and may result in multiple vertebral fractures (1). Osteoporosis Canada previously published a position statement about this (2).

Hence, the 2023 Osteoporosis Canada guideline (3) has recommended that those who are on denosumab therapy should remain on it long-term and ensure that therapy is uninterrupted.

The optimal duration of denosumab therapy is debatable. Studies have shown effectiveness of denosumab therapy with regards to improvements of BMD and fracture reduction, for up to 10 years (4). Beyond 10 years, there is a paucity of data.

Similar to bisphosphonates, long-term use of denosumab has been shown to be associated with osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) and atypical femur fractures (AFFs). As the incidence of AFF and ONJ are very low, it is difficult to determine whether the use of denosumab results in higher risks of AFF and ONJ (5).

Given the BMD decline and increased risk of multiple vertebral compression fractures with the discontinuation of denosumab, routine discontinuation of denosumab or taking a drug holiday after a predetermined duration is not recommended.

However, there may be situations when denosumab therapy needs to be discontinued. These may include intolerance or side effects to denosumab, patient preference, or a choice to stop therapy after long term therapy, given the fear of the risk of ONJ and AFF.

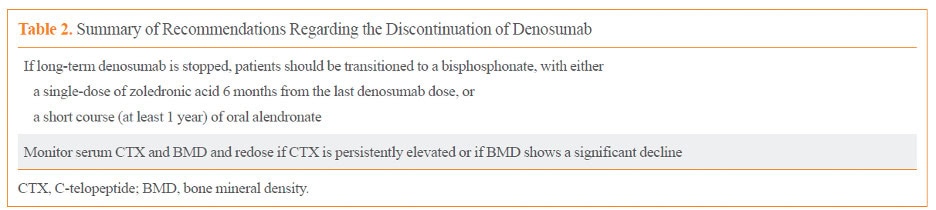

There have been many studies assessing the optimal method of discontinuing denosumab. After a review of the literature, the authors of the 2023 Osteoporosis Canada guideline recommended the following:

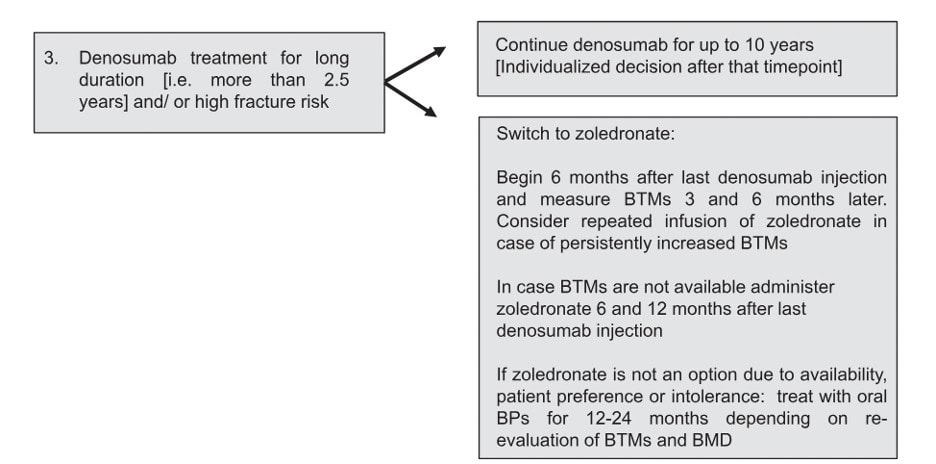

In line with the European Calcified Society (ECTC)’s statement (6), Osteoporosis Canada recommends that for those who have had 5 or more doses of denosumab (i.e. 2.5 years or more of treatment), the advice from a consultant with expertise in osteoporosis should be sought on how to transition to an alternative therapy.

There are reasons why Osteoporosis Canada did not provide specific recommendations for discontinuation of denosumab for these patients.

- The 2023 guideline is aimed for primary care physicians as opposed to specialists.

- Transition will likely involve IV bisphosphonate therapy, which may need to be arranged at a hospital or an infusion centre.

- Not all provincial/territorial drug coverage plans provide reimbursement for more than one dose of IV bisphosphonate annually.

- There is ongoing research in this field, and the best way for transitioning someone off denosumab is not currently known and may also change with time.

The ECTS recommends the following:

The Endocrine Society suggests that IV zoledronic acid be given at 8 months after the last dose of denosumab, and that the use of bone turnover markers may help determine when/if a second dose of zoledronic acid may be necessary (7).

A bone turnover marker target of C-terminal telopeptide (CTX) < 280 ng/L has been proposed as a target for adequate response after bisphosphonate therapy, by both the ECTS and Endocrine Society statements above. However, newer studies suggest that a lower target of CTX at 212 ng/L may be better at predicting possible bone loss (8). This shows that guidance on this matter will continue to evolve as new evidence continues to emerge.

The 2023 Osteoporosis Canada guideline has not made reference to or endorsed the use of bone turnover markers in the context of denosumab discontinuation. Although bone turnover markers may be available in most of Canada, it may not be universally funded, and hence, accessibility may be an issue. Although the lack of suppression after a dose of IV zoledronic acid may be an indication for the need of another dose, assessing the change in BMD may be a good alternative. The Korean Endocrine Society completed a review on this topic in 2022 (9). They recommend monitoring serum CTX and BMD, but that the decision to redose can be decided if the CTX is persistently elevated or if the BMD shows a significant decline.

The above recommendations from the various societies (ECTS, Endocrine Society, Korean Endocrine Society), are mostly based on expert opinion, rather than on established evidence. The divergence amongst the different recommendations reflects the differences in opinions amongst different experts.

Given that monitoring of BMD changes is an alternative to following bone turnover markers, and that not all Canadians have equal access to this test, we recommend that the decision to use bone turnover markers be made jointly by the patient and their physician.

Factors that may help with this decision include:

- Accessibility and coverage of the test

- Accessibility of IV zoledronic acid, including coverage for multiple doses within one year, if deemed necessary

- Other clinical evidence of bone stability (stability of BMD, absence or presence of new fractures)

- New evidence from research for or against the routine use of bone turnover markers for denosumab discontinuation

- Experience of the physician with interpretation of bone turnover marker results (aware of appropriate timing of test, fasting state, and consideration of factors influencing results).

References:

- Symonds C, Kline G. Warning of an increased risk of vertebral fracture after stopping denosumab. CMAJ. 2018 Apr 23;190(16):E485-E486. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.180115.

- https://osteoporosis.ca/position-statements/increased-risk-of-vertebral-fracture-after-stopping-denosumab/

- Morin SN, Feldman S, Funnell L, Giangregorio L, Kim S, McDonald-Blumer H, Santesso N, Ridout R, Ward W, Ashe MC, Bardai Z, Bartley J, Binkley N, Burrell S, Butt D, Cadarette SM, Cheung AM, Chilibeck P, Dunn S, Falk J, Frame H, Gittings W, Hayes K, Holmes C, Ioannidis G, Jaglal SB, Josse R, Khan AA, McIntyre V, Nash L, Negm A, Papaioannou A, Ponzano M, Rodrigues IB, Thabane L, Thomas CA, Tile L, Wark JD; Osteoporosis Canada 2023 Guideline Update Group. Clinical practice guideline for management of osteoporosis and fracture prevention in Canada: 2023 update. CMAJ. 2023 Oct 10;195(39):E1333-E1348. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.221647.

- Bone HG, Wagman RB, Brandi ML, Brown JP, Chapurlat R, Cummings SR, Czerwiński E, Fahrleitner-Pammer A, Kendler DL, Lippuner K, Reginster JY, Roux C, Malouf J, Bradley MN, Daizadeh NS, Wang A, Dakin P, Pannacciulli N, Dempster DW, Papapoulos S. 10 years of denosumab treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: results from the phase 3 randomised FREEDOM trial and open-label extension. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017 Jul;5(7):513-523. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30138-9.

- Everts-Graber J, Bonel H, Lehmann D, Gahl B, Häuselmann H, Studer U, Ziswiler HR, Reichenbach S, Lehmann T. Incidence of Atypical Femoral Fractures in Patients on Osteoporosis Therapy-A Registry-Based Cohort Study. JBMR Plus. 2022 Sep 22;6(10):e10681. doi: 10.1002/jbm4.10681.

- Tsourdi E, Zillikens MC, Meier C, Body JJ, Gonzalez Rodriguez E, Anastasilakis AD, Abrahamsen B, McCloskey E, Hofbauer LC, Guañabens N, Obermayer-Pietsch B, Ralston SH, Eastell R, Pepe J, Palermo A, Langdahl B. Fracture risk and management of discontinuation of denosumab therapy: a systematic review and position statement by ECTS. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020 Oct 26:dgaa756. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa756.

- Eastell R, Rosen CJ. Response to Letter to the Editor: “Pharmacological Management of Osteoporosis in Postmenopausal Women: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline”. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019 Aug 1;104(8):3537-3538. doi: 10.1210/jc.2019-00777.

- Grassi G, Ghielmetti A, Zampogna M, Chiodini I, Arosio M, Mantovani G, Eller Vainicher C. Zoledronate after denosumab discontinuation: Is repeated administrations more effective than single infusion? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2024 Apr 13:dgae224. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgae224.

- Tay WL, Tay D. Discontinuing Denosumab: Can It Be Done Safely? A Review of the Literature. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2022 Apr;37(2):183-194. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2021.1369.

Alcohol Intake and Bone Health

Dr. Adrian Lau, Dr. Rowena Ridout, Dr. Claudia Gagnon, Dr. Zahra Bardai, and Dr. Emma Billington.

Recommendations from Osteoporosis Canada Rapid Response Team.

What is a safe amount of alcohol intake?

The Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction (CCSA) published “Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report” in January 2023. These new 2023 guidelines tell us that there is a continuum of risk for alcohol-related harms. For healthy individuals, the risk is low with 2 drinks per week, moderate with 3-6 drinks per week, and increasingly high with more than 6 drinks per week.

Previously, Canada’s 2011 “Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines” recommended that to reduce our long-term health risks, women should have less than 10 drinks* per week, and men should have less than 15 drinks per week.

How does that relate to my bone health?

CCSA’s new guidelines do not specifically address the relationship between alcohol intake and fractures or osteoporosis.

Osteoporosis Canada’s guidance with regards to alcohol states: “Research shows an increased risk of osteoporosis for those who regularly consume 3 or more alcoholic drinks per day. Increased alcohol intake also contributes to increased risk for falls and is often associated with poor nutrition.” (https://osteoporosis.ca/risk-factors/)

Research shows that fracture risk is increased with having 3 or more alcoholic drinks per day. However, at this time, there are no studies available that provide information on whether lower alcohol intake (2 drinks per week or less), results in a reduced fracture risk. The relationship between alcohol intake and bone density or osteoporosis is unclear.

What should I do?

Even though an increased risk of fractures was not seen with 2 drinks per day (or 14 drinks per week), we recommend that you discuss these new 2023 CCSA recommendations with your physician to reduce your risk of alcohol-related consequences.

* Note: In Canada, a standard drink is:

· A bottle of beer (12 oz., 341 ml, 5% alcohol)

· A bottle of cider (12 oz., 341 ml, 5% alcohol)

· A glass of wine (5 oz., 142 ml, 12% alcohol)

· A shot glass of spirits (1.5 oz., 43 ml, 40% alcohol)

Alcohol Intake and Bone Health

Dr. Adrian Lau, Dr. Rowena Ridout, Dr. Claudia Gagnon, Dr. Zahra Bardai, and Dr. Emma Billington.

Recommendations from Osteoporosis Canada Rapid Response Team.

The Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction (CCSA) recently published “Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report” (1).

The key points from CCSA’s guidelines, published in January 2023, are:

- Among healthy individuals, there is a continuum of risk for alcohol-related harms where the risk is:

- Negligible to low for individuals who consume two standard drinks (see note) or less per week;

- Moderate for those who consume between three and six standard drinks per week; and

- Increasingly high for those who consume more than six standard drinks per week.

The 2023 guidelines are an update to the 2011 “Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines” (2), which previously recommended:

- Reduce your long-term health risks by drinking no more than:

- 10 drinks a week for women, with no more than 2 drinks a day most days

- 15 drinks a week for men, with no more than 3 drinks a day most days

Osteoporosis Canada’s guidance with regards to alcohol was in line with CCSA’s 2011 guidelines. It states, “Research shows an increased risk of osteoporosis for those who regularly consume 3 or more alcoholic drinks per day. Increased alcohol intake also contributes to increased risk for falls and is often associated with poor nutrition.” (3)

This recommendation stemmed from the results of a study by Kanis et. al. in 2005 (4), which analyzed the results of three prospective cohorts, including The Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMOS). It observed that there was no significant increase in the risk of osteoporotic or hip fractures when daily alcohol intake was 2 units or less. At this time, there are no studies available that provide any information on whether lower alcohol intake (2 drinks per week or less), results in a reduced fracture risk. The Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) (5), a commonly used tool in clinical practice endorsed by Osteoporosis Canada (6,7), considers daily alcohol consumption of 3 or more units to be a risk factor for fractures, as its modelling is based on data from Kanis et. al. (4).

The association between alcohol intake and bone density or osteoporosis is less clear. A meta-analysis by Godos et. al.(8), showed that consumption of up to two drinks per day was correlated with higher lumbar and femoral neck bone mineral density (BMD) values, while up to one drink was correlated with higher hip BMD compared to no alcohol consumption. On the other hand, a meta-analysis by Cheraghi et. al. (9) found that those consuming 0.5 to 1 alcoholic beverages per day had 1.38 times the risk of developing osteoporosis, while those consuming 1 to 2 per day had 1.34 times the risk of developing osteoporosis. Certainly, there are limitations of meta-analyses of observational studies. As well, BMD alone may not be the best indicator of overall bone health.

Although CCSA’s new guidelines (1) suggest that consuming more than 2 alcoholic drinks per week is associated with an increased risk of alcohol-related consequences, they did not specifically address the amount of alcohol intake that is associated with fractures or other bone-related consequences. Their research found that 3 to 6 standard drinks per week was associated with an increased risk of several types of cancer, while 7 or more was associated with an increased risk of heart disease or stroke.

Even though an increased risk of fractures was not seen with 2 drinks per day (or 14 drinks per week), we recommend that individuals discuss the new 2023 CCSA recommendations with their physicians, to review their targets on alcohol consumption to reduce the risk of alcohol-related consequences.

Note: In Canada (10), a standard drink is 17.05 millilitres or 13.45 grams of pure alcohol, which is the equivalent of:

· A bottle of beer (12 oz., 341 ml, 5% alcohol)

· A bottle of cider (12 oz., 341 ml, 5% alcohol)

· A glass of wine (5 oz., 142 ml, 12% alcohol)

· A shot glass of spirits (1.5 oz., 43 ml, 40% alcohol)

References:

- Paradis, C., Butt, P., Shield, K., Poole, N., Wells, S., Naimi, T., Sherk, A. et. al. The Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines Scientific Expert Panels. (2023). Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report. Ottawa, Ont.: Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction.

- Butt, P., Beirness, D., Gliksman, L., Paradis, C., & Stockwell, T. (2011). Alcohol and health in Canada: A summary of evidence and guidelines for low-risk drinking. Ottawa, Ont.: Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse.

- https://osteoporosis.ca/risk-factors/

- Kanis JA, Johansson H, Johnell O, Oden A, De Laet C, Eisman JA, Pols H & Tenenhouse A. Alcohol intake as a risk factor for fracture. (2005). Osteoporosis International. 16: 737–742

- https://frax.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/index.aspx

- Papaioannou A, Morin S, Cheung AM, et al. 2010 clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in Canada: summary. (2010). CMAJ. 182:1864–73.

- Lentle B, Cheung AM, Hanley DA, et al. Osteoporosis Canada 2010 Guidelines for the Assessment of Fracture Risk. (2011). Can Assoc Radiol J. 62(4): 243–250.

- Godos J, Giampieri F, Chisari E, Micek A, Paladino N, Forbes-Hernández TY, Quiles JL, Battino M, La Vignera S, Musumeci G, et al. Alcohol Consumption, Bone Mineral Density, and Risk of Osteoporotic Fractures: A Dose–Response Meta-Analysis. (2022). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 19:1515.

- Cheraghia Z, Doosti-Iranib A, Almasi-Hashianid A, Baigie V, Mansourniaf N, Etminang M, Mansourniah MA. The effect of alcohol on osteoporosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. (2019). Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 197:197-202.

- https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/substance-use/alcohol/low-risk-alcohol-drinking-guidelines.html

Scientific Advisory Council

Osteoporosis Canada’s rapid response team, made up of members of the Scientific Advisory Council, creates position statements as news breaks regarding osteoporosis. The position statements are used to inform both the healthcare professional and the patient. The Scientific Advisory Council (SAC) is made up of experts in Osteoporosis and bone metabolism and is a volunteer membership.